There is something invigorating and satisfying in knowing that one can actually conquer fear.

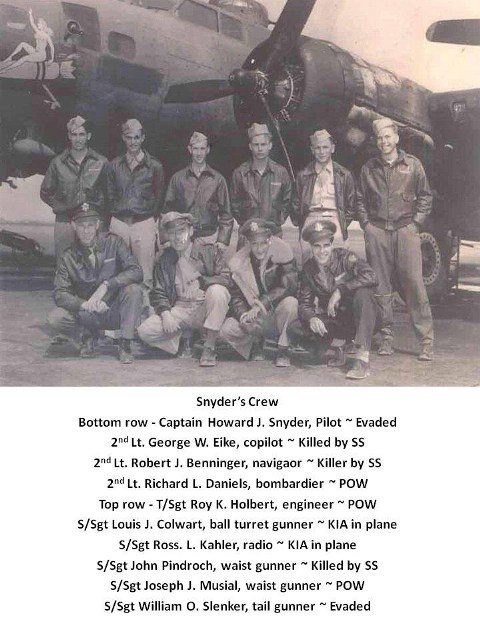

After I wrote about The Massacre of Saint Rémy, I was able to make contact with the son of Howard J. Snyder, pilot of the “Susan Ruth.” Three members of Snyder’s crew had been shot by SS troops in the Saint Rémy forest on the 22nd of April 1944.

A 29 year old pilot, Snyder came to Thurleigh to join the 306th Bombardment Group of the 8th AF on October 21st, 1943, the same month as my Dad. His crew would fly a new B-17, and Captain Howard was given the honor of naming her. It would be “Susan Ruth” after his bride of two years and their baby daughter Susan.

On February 8th, 1944 Snyder and his crew were briefed to bomb Frankfurt, Germany. They had flown to Frankfurt and back once before almost uneventfully, returning on only three engines, and Snyder wasn’t unusually nervous about this mission. As the ship joined the formation of 750 bombers, he and his crew joked over the intercom about their partying the night before. It was a beautiful day at 24,000 feet with an almost solid layer of billowing white clouds beneath them.

Once they hit the target, they met the usual intense flak. One burst pitted the windshield right in front of the pilots.

“Flak doesn’t scare me anymore, but I still feel my heart speed up as if it were thrown into high gear. My pulse throbs as if the pressure would burst the veins. the sweat runs down my back and sides in small streams. I feel hot and flushed and all of my actions speed up, making my normal movements seem like slow motion.

“Whenever I leave a heavy flak area I cool down as if after some violent and heavy physical exertion. I don’t think I can actually say I enjoy the sensation, but I can say that I don’t dislike it. There is something invigorating and satisfying in knowing that one can actually conquer fear.”

When the “Susan Ruth” had been flying back toward base for about an hour a pack of German fighters suddenly attacked mercilessly. The celestial dome above the pilot’s head blew up. Pieces of equipment and parts of the ship were flying about the cockpit, striking his feet and legs. The oxygen cylinders exploded and flames were everywhere.

When the “Susan Ruth” had been flying back toward base for about an hour a pack of German fighters suddenly attacked mercilessly. The celestial dome above the pilot’s head blew up. Pieces of equipment and parts of the ship were flying about the cockpit, striking his feet and legs. The oxygen cylinders exploded and flames were everywhere.

Snyder thought he must have blacked out for a moment. Then it took a few seconds for him to begin to react to the terror that was unfolding around him. He tried to extinguish the flames but when he realized that it would be impossible to save his ship he put it on autopilot. There was no way for him to get to the back of the plane so he called through the intercom for the crew to jump. After he made sure that the other three men in the front had gone through the nose hatch, Snyder fell out after them.

“It was only natural to wonder if the chute would open. I knew soon enough, for as the air caught and filled the chute, the jerk nearly snapped my neck off. The rushing air roaring in my ears stopped suddenly and a most wonderful and peaceful quiet settled over me. It seemed as if I had come out of that hell above into a heaven of peace and rest. Up above I could now hear the roar of the Forts mingled with the angry rasping roar of the fighters. But with the peaceful country coming up to meet me, baked in the sunshine, the war and all that had happened only a few seconds before seemed like a bad dream long ago.”

When Howard Snyder wrote these words he was in hiding, and it was just a few weeks after his jump from the doomed “Susan Ruth.” What he may not have realized at the time is that German machine gunners were spraying the men who were falling. The wind blew his parachute one or two kilometers out of their range, and he barely escaped the bullets.

The parachute became entangled in an oak tree twenty feet off the ground, and he was rescued by sympathetic farmers who brought a ladder to get him down. Other than an injured ankle and a few burns he was unharmed. For the next few months the underground network in Belgium moved him each time the Germans came too close. In July he was taken to a resistance camp in Fagne, France, just at the border with Belgium, and was incorporated into the French Maquis. There he stayed as a guerrilla fighter until he was liberated on September 2nd, 1944 by the 1st U.S. Army 9th Infantry Division. It was then that he was able to wire Ruth to tell her that he was okay. He was back in London by October.

You have to give credit to the Captain. He wrote that once the cockpit filled with flames he was absolutely terrified. He tried to scream but the sound died in his throat. He looked over to his copilot who seemed absolutely mad. By sheer will power, he forced himself to regain control and just went on more from instinct, he admitted, than anything else.

At a time like that the difference between life and death might just be the seconds between panic and a steady response. One of Snyder’s crew members later described how the morning had begun: “Captain Snyder thought about his one and half-year-old daughter, his wife Ruth and his coming second baby. He crossed himself like most of the crew members when the engines hurled and the plane took off.”

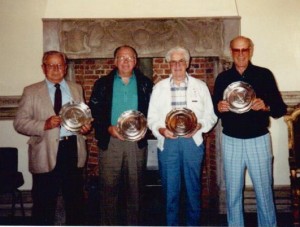

1989 ~ Joe Musial, Bill Slenker, Roy Holbert, and Howard Snyder. Richard Daniels died that same year at home.

Of the ten men on board, two were killed instantly while still on the plane. Three were murdered two months later at Saint Rémy.

Two evaded capture and three became German POWs. These men went home to their families after the war was over.

The survivors of the “Susan Ruth” have never forgotten their friends who died that year. In 1986, Captain Snyder and Joseph Musial returned to Belgium to pay homage to their companions. They and their family members have since returned to visit a memorial there.

2015 Update: Steve Snyder, the son of Howard J. Snyder, has published a book about his Dad’s World War II experiences. See my post on Shot Down.

Harvey Hall

Posted at 18:01h, 18 FebruaryDear Mrs (Patricia Allen) Digeorge,

I am the old guy from the Summerlin Institute class of ’49. I met you and your sister at the SI 125th reunion last November (2012) You and your sister flattered me by saying I didn’t look old enough to have graduated in 1949. We had a good conversation about your father whom I knew slightly. I remember when he was an active businessman in Bartow. I enjoyed reading this update on your book, and I hope to read it when it is published.

Harvey Hall