21 Feb Eldon E. Posey

Eldon E. Posey left college in the summer of 1941 to join the Army Air Corps. By April of 1942, he was assigned as a fighter pilot to the 59th Squadron, 33rd Pursuit Group stationed in Philadelphia. Posey was placed on special assignment with the Navy in September 1942 to test P-40 fighter plane takeoffs from an aircraft carrier. While on service with the Navy, Posey was trained in navigation and map making. He had a special talent for this, one that was put to good use throughout his military career.

Posey’s fighter group participated in some of the most brutal campaigns of the war, in North Africa and in Sicily. Twice he was forced to land his damaged plane in enemy territory and, with help, was able to rejoin his outfit each time.

In September 1943 Posey went back to the states to the 56th Fighter Squadron 54th Fighter Group, in Bartow, Florida (my hometown!) A special photo-reconnaissance unit was put together to train fighter pilots to pinpoint primary targets for the air force bombers in Europe.

It was at this time that Posey married Miss Christine Kenner Johnson whom he had met and courted while she was a student at the University of Tennessee. They lived in an apartment in Bartow for a short time before Posey was sent overseas again.

1944 and back in Europe, Posey’s first photo-reconnaissance assignment was to an island in the Baltic Sea off the coast of N.E. Germany, Peenemünde, where Germany was building two new and powerful weapons there, the V-1 and V-2 rockets.

1944 and back in Europe, Posey’s first photo-reconnaissance assignment was to an island in the Baltic Sea off the coast of N.E. Germany, Peenemünde, where Germany was building two new and powerful weapons there, the V-1 and V-2 rockets.

Posey flew on the March 6th mission to Berlin, the day that the Liberty Lady was forced to make an emergency landing on the Swedish island of Gotland.

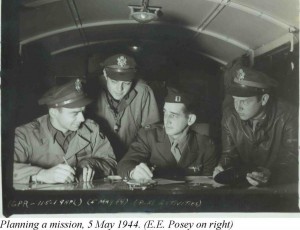

Posey was soon named Operations Officer of his Fighter Group. He coordinated the fighters’ participation with the bombers on their bombing missions. By that time all operations were focused on plans for Operation Overlord, D-Day.

On May 13, 1944, Posey in his P-51 Mustang “Z Hub” landed in Sweden. He always disputed the report written in “Making for Sweden” but insisted that he had been ordered to never discuss this experience and simply would not elaborate.

“Making for Sweden” details that Posey was forced to Sweden for lack of fuel. We do know, according to Mrs. Posey, that when he landed he wasn’t sure whether or not he was in a German-occupied country, and to be in Sweden was a huge relief.

Posey boarded with a Swedish family during his short internment. One evening he was out for dinner with a friend at a restaurant in Stockholm and met up with a Nazi spy that was on the OSS Watch List. He reported in with Herman Allen at the American Legation about this incident afterward.

Posey was ordered back to England after being in Sweden only twenty-four days. My theory is that once it was discovered where he was, the Air Force did everything they could to get him back into action as quickly as possible. He was flown to Leuchers, Scotland, in civilian dress on Bernt Balchen’s courier service.

Toward the end of the war, during the Battle of the Bulge, Posey was shot down again, and this time he was wounded. The bones in his leg were shattered, and this injury would haunt him for the rest of his life.

This decorated WWII hero flew well over 100 combat missions. He was smart about his tactics and that is why he was able to stay alive. He personally contributed to the war effort in an important way with his reconnaissance activities.

After the war, Posey went on to earn his Ph.D. in mathematics and spent most of his years at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He died at the age of 87, and his University published an account of his distinguished career there. The article also mentions the book that Posey wrote, “World War II Experiences and Memories.” It is worth reading, an excellent history of the North African and European campaigns, and can be downloaded at this link.

Joy

Posted at 17:57h, 22 FebruarySo he returned to duty in the European theatre? Internees usually were supposed to have agreed not to return to the same theatre of war. Most came back to the US and were reassigned to other places, such as the Pacific or Far East. There was one internee in Sweden who actually was interned twice in Sweden, despite the supposed agreement. I will have to look up the Making for Sweden account. My fathers crew also was not sure whether they were in Denmark or Sweden until they were convinced by the Swedes saying “Sverige. Sverige” and showing their cap markings with the Swedish insignia.

Pat

Posted at 10:06h, 23 FebruaryI have also read that the policy was that internees were not to return to where they came from. However, in addition to this fighter pilot who went right back to his squadron in order to join the D-Day invasion, the pilot and co-pilot of the Liberty Lady both went back to Thurleigh toward the end of 1944 and completed their 30 missions. They were asked not to talk about their internment. At that time experienced pilots were at a premium so that may be why the “rule” was adjusted.

Pearle Wood

Posted at 15:46h, 23 FebruaryWow! Thanks, Patti! Recently, I became reinterested in WWII while visiting the Camp Gordon Johnston WWII Museum in Carrabelle where I also saw a copy of a picture with Loyal Frisbee and Gen. Van Fleet! Many troops were trained for the D Day invasion at Carrabelle, as well as here on St. George Island! Take care. Pearle