02 Jan Washington Goes to War

(1988) In his book Washington Goes to War, newscaster and journalist David Brinkley tells the story of the transformation of the capital city during World War II.

(1988) In his book Washington Goes to War, newscaster and journalist David Brinkley tells the story of the transformation of the capital city during World War II.

Mr. Brinkley writes nothing about his personal military involvement in the war. I finally found in a philly.com article explaining that in 1940, he volunteered for the Army. A year later he was misdiagnosed with a kidney ailment and honorably discharged. He then worked in Atlanta and Nashville for UPI (United Press International) before moving to Washington, D.C. as a reporter for the NBC radio network.

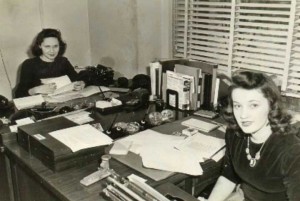

His book is copiously researched and begins with a history of the creation of the city itself. What interested me the most was how it changed from a sleepy town to the chaotic center of the free world. In 1941 my mother, Hedy Allen, arrived in Washington to be one of the vast number of “government girls” who came to work as stenographers, typists, and file clerks for the myriad of new government agencies that were popping up every week.

I laughed so many times during the book at Brinkley’s sense of humor. “Six months into the war, there were so many new agencies, all known by their initials that nobody could keep them straight.” OPC, OWI, WPB, OPA, WMC, BEW, NWLB, ODT, WSA, OCD, OEM … and I will add those from the OSS since that’s where my mother worked … COI, SI, X-2, SO, OG, R&A, MO. The secretary of the interior, Harold Ickes, was also director of the Office of Petroleum Coordination. At a news conference when asked about an OPC ruling, he answered, “I can’t speak for the OPC.” That is, until an aide whispered in his ear, “You are the director of the OPC.” Ickes was confused by all the initials too.

So, all these initials needed government employees, and most of them were women. In the beginning civil service exams were required (my mother took one) but they were dropped. Took too much time. The government advertised in newspapers all over the country for anyone who had a high school diploma and could type. $1440 a year.

The women (if they didn’t already have a job, and thank goodness my mother did) went to a mass receiving station above a dime store where they were interviewed. There were never enough workers to feed the agencies.

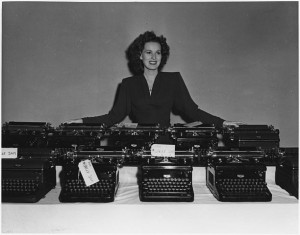

And there were never enough typewriters. By mid-1942 the government said it was 600,000 typewriters short. The companies that had been making typewriters had been diverted to war production. The OWI (Office of War Information) began a “Send your typewriter to war” campaign. Maureen O’Hara posed behind a table piled with typewriters. Each had a tag that read, “For Uncle Sam.”

Taking time off between the shooting of scenes at the RKO Studios in Hollywood, Miss O’Hara helped collect more than 70 typewriters for future use by the Army, Navy, and Marines. (This media is available in the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Problem was, not that many people were willing to hand over their typewriters. Plus, the ones that came in with their standard 12 inch carriages often weren’t the right size. These new agencies were using new forms up to 18 inches wide.

The next crisis was paper. When the war started, the government owned $650,000 worth of printing and reproducing equipment. In less than a year it had $50 million worth. There wasn’t enough paper to keep all these machines going, and there wasn’t enough space to store the records they created. After spending two weeks in the National Archives going through just some of the papers of one WWII office (X-2 Stockholm) I believe it!

Six months after Pearl Harbor more than half the young women hired as typists and stenographers had quit and gone home. They had been hired but were never given anything useful to do.

“It was simply the way the government worked, in both war and peace, although in wartime it was worse. The single fact most clearly differentiating government employers from private employers was, always, that government agencies did not have to earn their money. Congress simply handed it over every year and almost always more than the year before, so it was there to be spent and it was unthinkable not to spend it. Nobody in government ever benefited in any way from saving money. Whatever was not spent had to be handed back to the Treasury and if an agency had money left over at the end of one year, how could it ask Congress for more money the next year?”

Perhaps not much has changed in the past seventy years!

For anyone with a connection to Washington D.C. and/or World War II, I highly recommend Brinkley’s book.

Washington Goes to War at amazon.com

No Comments